The cultural figure of the bohemian first emerged in 1830s Paris when a group of struggling writers and artists appropriated the identity popularly associated with the Romani people ("Gypsies") as rootless nomads whose unconventional lifestyle was taken as a model for revolution from social restraint. These Parisian writers and artists used the name of the Romani homeland—Bohemia—to describe their self-imposed exile from bourgeois culture and the sacrifices they made for their art. By the 1840s, the French novelist and poet Henri Murger would record the exploits of the bohemians of Paris's Latin Quarter in a series of semi-autobiographical vignettes that he collected into a successful play, La Vie de la boheme (1849), and an equally successful book, Scenes de la vie de Boheme (1850). Murger's book, sections of which were translated by Charles Astor Bristed as "The Gypsies of Art" in New York's Knickerbocker magazine in 1853, helped to spread the image of the bohemian artist throughout the United States. The British writer William Makepeace Thackeray also popularized bohemianism in his 1848 novel, Vanity Fair, the title of which would inspire a New York-based bohemian literary weekly of the same name.

The cultural figure of the bohemian first emerged in 1830s Paris when a group of struggling writers and artists appropriated the identity popularly associated with the Romani people ("Gypsies") as rootless nomads whose unconventional lifestyle was taken as a model for revolution from social restraint. These Parisian writers and artists used the name of the Romani homeland—Bohemia—to describe their self-imposed exile from bourgeois culture and the sacrifices they made for their art. By the 1840s, the French novelist and poet Henri Murger would record the exploits of the bohemians of Paris's Latin Quarter in a series of semi-autobiographical vignettes that he collected into a successful play, La Vie de la boheme (1849), and an equally successful book, Scenes de la vie de Boheme (1850). Murger's book, sections of which were translated by Charles Astor Bristed as "The Gypsies of Art" in New York's Knickerbocker magazine in 1853, helped to spread the image of the bohemian artist throughout the United States. The British writer William Makepeace Thackeray also popularized bohemianism in his 1848 novel, Vanity Fair, the title of which would inspire a New York-based bohemian literary weekly of the same name.

At the same time that the broader Atlantic world was being exposed to bohemianism through the works of Murger and Thackeray, the American writers Henry Clapp, Jr., and Ada Clare were experiencing bohemia first-hand in Paris and London, which they would write about for The Saturday Press (in "A New Portrait of Paris" and "A Bohemienne") after returning to the United States and attempting to recreate the bohemian Latin Quarter at Charles Pfaff's beer cellar and literary salons across Manhattan. Debates over the merits of bohemianism appeared in The New York Times, Harper's Weekly, The Roundtable, and other American periodicals as the figure of the bohemian was embraced by writers and artists throughout New York. The Civil War ultimately dampened this enthusiasm for bohemian experimentation with life and art: the economic turmoil associated with the war led, in part, to the failure of the two periodicals most closely associated with the bohemian cause—Vanity Fair and The Saturday Press—just as the consequences of the war itself scattered bohemian writers and artists across the country. From about 1855 to 1865, however, the United States' first bohemians "transplanted from the mother asphalt of Paris" (as William Dean Howells put it) an enduring cultural formation that has been a consistent facet of American culture ever since.

The timeline in this section of The Vault at Pfaff's selects a few highlights from the story of the antebellum bohemians as a way to introduce readers to a larger set of issues that can be explored more fully in the Works section of this site. Similarly, we are in the process of identifying the locations where the antebellum bohemians lived and worked on an 1860 map of New York City in an effort capture the scale of the bohemian community. This GIS map is based on a digital reproduction of Map of the City of New-York and Its Environs from Actual Survey under the Direction of H. F. Walling (New York, NY: S. B. Tilden, 1860), which has been generously provided by the David Rumsey Map Collection. Stephanie Blalock's history of Charles Pfaff's restaurant and lager beer saloon is published in collaboration with Lehigh University Press.

To learn more about the people of bohemian New York and their relationships with one another please visit those respective sections of the site.

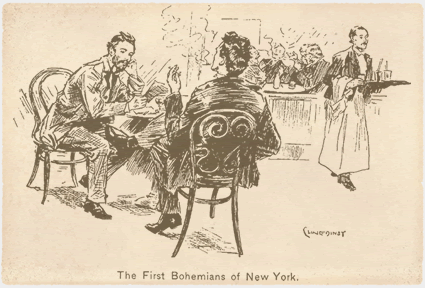

The images on this page is by Benjamin West Clinedinst and was originally an illustration for "Urban and Suburban Sketches: The Bowery and Bohemia," which was published in Scribner's Magazine in January 1894.